John Szarkowski, Curator of Photography, Dies at 81

I just found this on the NY Times website. The passing of many of the influential people in the world of photography makes me wonder who, of the contemporary photographers, educators, curators and critics, will carry on the work of the ones who forged how we think and what we know about photography. From The New York Times

John Szarkowski, a curator who almost single-handedly elevated photography’s status in the last half-century to that of a fine art, making his case in seminal writings and landmark exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, died in on Saturday in Pittsfield, Mass. He was 81.

Richard Avedon/Courtesy Richard Avedon Foundation

John Szarkowski in 1975.

The cause of death was complications of a stroke, said Peter MacGill of Pace/MacGill Gallery and a spokesman for the family.

In the early 1960’s, when Mr. Szarkowski (pronounced Shar-COW-ski) began his curatorial career, photography was commonly perceived as a utilitarian medium, a means to document the world. Perhaps more than anyone, Mr. Szarkowski changed that perception. For him, the photograph was a form of expression as potent and meaningful as any work of art, and as director of photography at the Modern for almost three decades, beginning in 1962, he was perhaps its most impassioned advocate. Two of his books, “The Photographer’s Eye,” (1964) and “Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures From the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art” (1973), remain syllabus staples in art history programs.

Mr. Szarkowski was first to confer importance on the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand in his influential exhibition “New Documents” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967. That show, considered radical at the time, identified a new direction in photography: pictures that seemed to have a casual, snapshot-like look and subject matter so apparently ordinary that it was hard to categorize.

In the wall text for the show, Mr. Szarkowski suggested that until then the aim of documentary photography had been to show what was wrong with the world, as a way to generate interest in rectifying it. But this show signaled a change.

“In the past decade a new generation of photographers has directed the documentary approach toward more personal ends,” he wrote. “Their aim has been not to reform life, but to know it.”

Critics were skeptical. “The observations of the photographers are noted as oddities in personality, situation, incident, movement, and the vagaries of chance,” Jacob Deschin wrote in a review of the show in The New York Times. Today, the work of Ms. Arbus, Mr. Friedlander and Mr. Winogrand is considered among the most decisive for the generations of photographers that followed them.

As a curator, Mr. Szarkowski loomed large, with a stentorian voice and a raconteurial style. But he was self-effacing about his role in mounting the “New Documents” show.

“I think anybody who had been moderately competent, reasonably alert to the vitality of what was actually going on in the medium would have done the same thing I did,” he said several years ago. “I mean, the idea that Winogrand or Friedlander or Diane were somehow inventions of mine, I would regard, you know, as denigrating to them.”

Another exhibition Mr. Szarkowski organized at the Modern, in 1976, introduced the work of William Eggleston, whose saturated color photographs of cars, signs and individuals ran counter to the black-and-white orthodoxy of fine-art photography at the time. The show, “William Eggleston’s Guide,” was widely considered the worst of the year in photography.

“Mr. Szarkowski throws all caution to the winds and speaks of Mr. Eggleston’s pictures as ‘perfect,’ ” Hilton Kramer wrote in The Times. “Perfect? Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly.” Mr. Eggleston would come to be considered a pioneer of color photography.

By championing the work of these artists early on, Mr. Szarkowski was helping to change the course of photography. Perhaps his most eloquent explanation of what photographers do appears in his introduction to the four-volume set “The Work of Atget,” published in conjunction with a series of exhibitions at MoMA from 1981 to 1985.

“One might compare the art of photography to the act of pointing,” Mr. Szarkowski wrote. “It must be true that some of us point to more interesting facts, events, circumstances, and configurations than others.”

He added, “The talented practitioner of the new discipline would perform with a special grace, sense of timing, narrative sweep, and wit, thus endowing the act not merely with intelligence, but with that quality of formal rigor that identifies a work of art, so that we would be uncertain, when remembering the adventure of the tour, how much our pleasure and sense of enlargement had come from the things pointed to and how much from a pattern created by the pointer.”

Thaddeus John Szarkowski was born on Dec. 18, 1925, in Ashland, Wis., where his father later became assistant postmaster. Picking up a camera at age 11, he made photography one of his principal pursuits, along with trout fishing and the clarinet, throughout high school.

He attended the University of Wisconsin, interrupted his studies to serve in the Army during World War II, then returned to earn a bachelor’s degree in 1947, with a major in art history. In college, he played second-chair clarinet for the Madison Symphony Orchestra, but maintained that he held the post only because of the wartime absence of better musicians.

As a young artist in the early 1950s, Mr. Szarkowski began to photograph the buildings of the renowned Chicago architect Louis Sullivan. In an interview in 2005 in The New York Times, he said that when he was starting out, “most young artists, most photographers surely, if they were serious, still believed it was better to work in the context of some kind of potentially social good.”

The consequence of this belief is evident in the earnestness of his early pictures, which come out of an American classical tradition. His early influences were Walker Evans and Edward Weston. “Walker for the intelligence and Weston for the pleasure,” he said. In 1948, Evans and Weston were not yet as widely known as Mr. Szarkowski would eventually make them through exhibitions at MoMA.

By the time Mr. Szarkowski arrived at the museum from Wisconsin in 1962 at the age of 37, he was already an accomplished photographer. He had published two books of his own photographs, “The Idea of Louis Sullivan” (1956) and “The Face of Minnesota” (1958). Remarkably for a volume of photography, the Minnesota book landed on The New York Times best-seller list for several weeks, perhaps because Dave Garroway had discussed its publication on the “Today” program.

When Mr. Szarkowski was offered the position of director of the photography department at the Modern, he had just received a Guggenheim Fellowship to work on a new project. In a letter to Edward Steichen, then curator of the department, he accepted the job, registering with his signature dry wit a reluctance to leave his lakeside home in Wisconsin: “Last week I finally got back home for a few days, where I could think about the future and look at Lake Superior at the same time. No matter how hard I looked, the Lake gave no indication of concern at the possibility of my departing from its shores, and I finally decided that if it can get along without me, I can get along without it.”

A year after arriving in New York, he married Jill Anson, an architect, who died on Dec. 31. Mr. Szarkowski is survived by two daughters, Natasha Szarkowski Brown and Nina Anson Szarkowski Jones, both of New York, and two grandchildren. A son, Alexander, died in 1972 at age 2.

Among the many other exhibitions he organized as a curator at the Modern was “Mirrors and Windows,” in 1978, in which he broke down photographic practice into two categories: documentary images and those that reflect a more interpretive experience of the world. And, in 1990, his final exhibition was an idiosyncratic overview called “Photography Until Now,” in which he traced the technological evolution of the medium and its impact on the look of photographs.

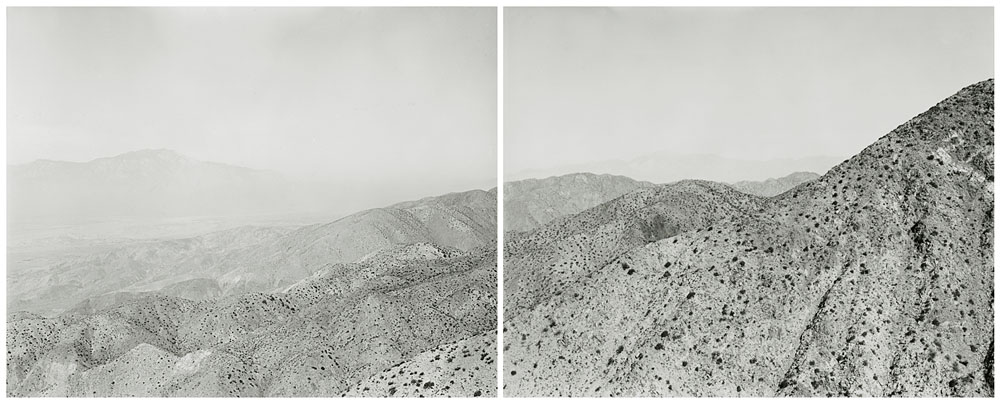

In 2005, Mr. Szarkowski was given a retrospective exhibition of his own photographs, which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, touring museums around the country and ending at the Museum of Modern Art in 2006. His photographs of buildings, street scenes, backyards and nature possess the straightforward descriptive clarity he so often championed in the work of others, and, in their simplicity, a purity that borders on the poetic.

From his own early photographs, which might serve as a template for his later curatorial choices, it is easy to see why Mr. Szarkowski had such visual affinity for the work of Friedlander and Winogrand.

When asked by a reporter how it felt to exhibit his own photographs finally, knowing they would be measured against his curatorial legacy, he became circumspect. As an artist, “you look at other people’s work and figure out how it can be useful to you,” he said.

“I’m content that a lot of these pictures are going to be interesting for other photographers of talent and ambition,” he said. “And that’s all you want.”

This new picture from my

This new picture from my