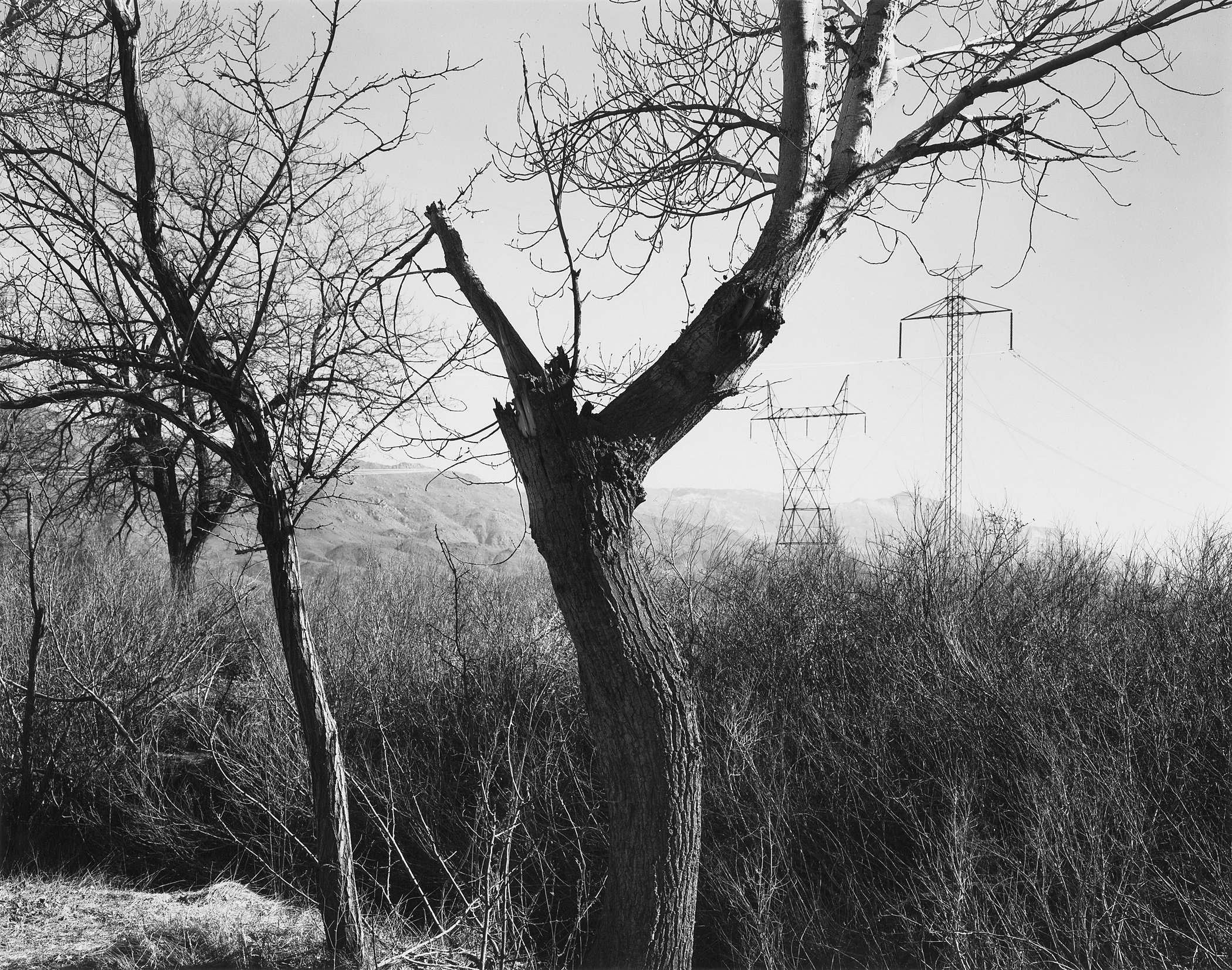

Go West: Looking Back, Looking In

Early Landscapes from 2001-2010

I am the adventurer on a voyage of discovery, ready to receive fresh impressions, eager for fresh horizons—to identify myself in, and unify with, whatever I am able to recognize as a significantly part of me: the ‘me’ of universal rhythms . —Edward Weston, 1932

Is it the vastness and the openness of the American West, where everything seems to be in a heightened state, the reason why so many people go there seeking some kind of spiritual deliverance? Is there something inexplicable in that environment that enables opening and receptiveness in people who go there looking for it?

These images are from a 2015 group exhibition, with additional selections from my archive of earlier work. In assembling this show, I looked at landscape photographs I had made that span a nearly 15-year period. There were years when I was interested in seeing certain things a certain way, or returning to specific places to create longer-term bodies of work. While I was photographing and showing work with that kind of project-based focus, the turn back toward the Western landscape, and to what I could learn and discover photographing there, remained consistent. The pictures here are not connected to a larger series with self-imposed restraints, and freed from needing to fit into a larger narrative, they are the result of simply being receptive to what that landscape offers.

I've spoken in the past about the act of photographing as something of a meditation—in full awareness of everything around me, the picture is a result of actual connection with what I am photographing. Photographing the landscape becomes less about geological, geographical, sociological, or topological importance, and more about inner self-awareness and interconnectedness.

These are all landscape photographs, and while we might look at them and think we are seeing a record of the majestic or subtle beauty of the natural world, that is not the subject. The subject is not what is in the picture. The subject is out of view, and if anything, the things in the picture are just adjectives describing a state of place and of physical existence. Think of them, rather, as a recording of a place where an interaction between me and the real subject happened—something like a visual mantra, a point of intense focus for something that is both enormous and fleeting. It has been nearly 100 years since Edward Weston spoke of universal rhythms, but hasn’t that always been, and continues to be, the what and why we’re searching for?

— Richard Boutwell

August 2015